flickr photo shared by mrkrndvs under a Creative Commons ( BY-SA ) license

Here is a collection of reflections from some of the sessions I attended at the Leading a Digital Schools Conference held at Crown Casino on 25th, 26th and 27th of August.

It’s Time to Refocus: Creating a Broader Learning Context is the Key to Using Technology Effectively – Ted McCain

With the progression from punch cards through to thought controlled computers, technology is progressively becoming easier to use, with the ultimate goal being for it to disappear. Ted McCain posed the question, is the focus on technology the wrong thing? Our focus, according to McCain, instead should be in developing the cognitive skills required to use the available technology at any given time effectively. These skills were captured within the nine I’s:

- Interpersonal

- Intrapersonal

- Independent Problem Solving

- Interdependent Collaboration

- Information Investigation

- Information Communication

- Imagination Creativity

- Innovation Creativity

- Internet Citizenship

At the heart of these skills is a focus on student-centred facilitation, active learning, that focuses on discovering, rather than being told. McCain’s focus on the problem reminded me of Ewan McIntosh’s idea of problem finders, while I also wonder how McCain’s skills would compare with Doug Belshaw’s essential elements of digital literacies.

Leading Effective Teams in Schools – Steve Francis

Steve Francis session focused on the importance of team. The benefits that he sighted were: efficiency, effectiveness and consistency. Francis identified four keys for this to occur:

- Leadership

- Purpose

- Trust

- Processes

Without any of these ingredients, the notion of team becomes hamstrung. For example, you may have clear leadership, with processes in place to develop a high level of trust. However, when people are forced together around a contrived purpose then teams often falter.

On the flipside of this, Francis highlighted five specific dysfunctions associated with teams:

- Absence of trust

- Fear of conflict

- Lack of commitment (to team)

- Avoidance of accountability

- Inattention to results

What was interesting was what came out of the opportunities to work with others. In my team were a couple of teachers from Bray Park in Queensland. Some of the observations made were that the biggest team in a school is the school and it is this team that we need to get right first. In regards to leadership, this is often set by those who set the standard, rather than those who carry the titles. In addition to this, we may be a leader above our pay grade, but we are never a leader above our professional grade.

Are Schools Like Dinosaurs – Steve Francis

The focus of THe keynote was change. He touched on a number of facets of change, including the different stages:

- Information

- Personal

- Implementation

- Impact

- Collaboration

- Refinement

And some of sins associated with implementing change:

- Keep doing what you have always done

- Ignore it … trends come and go

- Throw out the baby with the bathwater

- Jump on EVERY bandwagon

- Waste your time and energy whinging

- Procrastinate until it is MASSIVE

- Fake it … do what you’ve always done but call it something else

He argued that one of the main reasons that schools have not really changed is because they err towards incremental change, rather than transformative change. The problem is that significant change takes GIANT leaps that can’t be achieved through incremental steps.

He gave the example of when bird flu broke out in Hong Kong and how students were forced to stay at home. This forced he and his colleagues to rethink what it means to teach. In the process many sacred cows were called out.

Francis argued that we are coming to a tipping point where transformative change is inevitable.

Encouraging Innovation: Creating an Enabling School Culture – Christine Haynes

Christine Haynes posed the key question, “if technology enables learning, who enables the technology?” Building on Dan Pink’s notion of autonomy, mastery and purpose, she focused on the notions of self-help, collaboration and coordination. With these ideas in mind, she focused on the following prompts:

- I can help myself

- We help each other

- We proactively move towards a shared strategic vision

These prompts are central to the creation of a culture of change.

Associated with this, Haynes provided a range of questions to consider, such as how you celebrate failure, what subscriptions have you got, how will you incorporate digital citizenship, what ways are you modelling Creative Commons, who manages the budgets, are there appropriate policies in place and how are students involved as contributor?

Haynes covered many topics in her presentation and left a lot to consider.

Shifting to Deeper Learning – Derek Wenmoth

There are many fads which come and go in education, but according to Derek Wenmoth, the one question that remains is, “who owns the knowledge?” The head of CORE Education, Wenmoth argued that if we are going to admit that we need to go deeper, then we need to recognise what is happening in our classrooms today starts from a very shallow base.

Wenmoth touched on a number of topics, including New Pedagogies for Deeper Learning, Michael Fullan’s 6C’s, the integration of learning and technology, as well as the need for more wicked problems. He closed the keynote with a series of calls to:

- Stop prescribing and start personalising.

- Stop thinking that teachers are the problem, empower them to be a part of the journey.

- Rethink the structures in our school and think more globally and connected.

- Stop forcing kids to l;earn what we want, instead provide more authenticity

- Stop bench-marking everything against test scores

Wenmoth left with one last provocation, “we need to start inventing the excellence of the future.”

What Maker Kids, Tom Hanks and PAX Taught Me About Creativity – Adrian Camm

For his keynote, Adrian Camm focused on five features in developing a learning culture:

- Create a shared vision

- Shift from passive to active

- Provide permission to innovate

- Make your default response ‘yes’

- Tell people they are awesome

The highlight was working collaboratively as the room to come up with ideas ‘Instead Of‘ the usual.

Creating a Vision for Learning – Adrian Camm

One of the biggest problems with vision statements is that they are often created by the board and placed on a school’s website. The issue with this is that staff (and students) have little ownership over the various ideas. Adrian Camm unpacked what it means to create a true vision for learning.

To shift this thinking, we first need to understand the different types of personal and collaborative visions. For Camm, he differentiates between a mantra, a personal vision, a collective statement and a shared idea of what that statement actually means. The reality is if you do not have buy in then you can not have agreement. So although a school may have a motherhood statement, it is important for people to also have voice about what it might mean in reality.

Camm’s advice was to start small and expand from there. He outlined ten steps:

- Invite people to be involved.

- Brainstorm inquiry probes designed to dig deeper.

- Reduce the number of probes to eight.

- Set a group for each probe.

- Group works through the probe.

- Final vote on what is important.

- Writing an initial draft.

- Forming a final draft

- Communicating it out.

- Preparing for action.

A resource that Camm suggested to support this process is Gamestorming.

The next step once this is done is to map the curriculum in order to make the vision real. Camm showed how his school used Rubicon Atlas and UbD model to do this.

My three take-aways from the conference were:

- A strong PLN is integral for fostering collaborative projects

- A good keynote involves a mixture of personal content, a clear narrative and the opportunity to meet new people.

- Communicating with people from different regions is a powerful in uncovering those elements which we can sometimes take for granted.

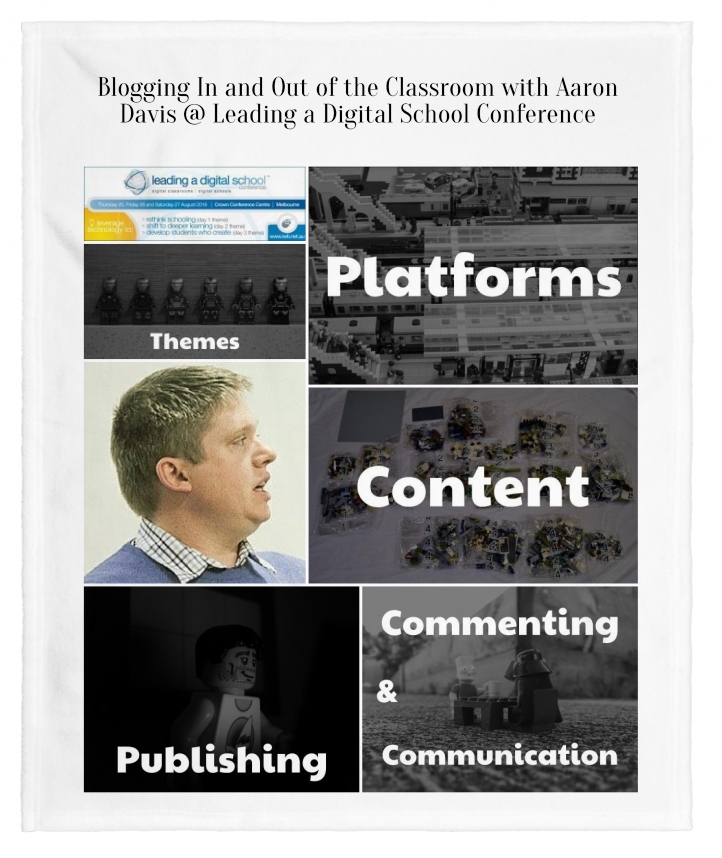

For a Storify of the event, click here. While here are the links to my presentation on blogging and integrating technology in the classroom.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.