Responding to Holly Clark, I explain why I cringe when the concept of digital literacy is replaced with fluency, subsequently overlooking the plurality of digital literacies.

There has been a lot written about digital literacy of late, much of the conversation stemming from the Engagement in a Time of Polarisation MOOC and danah boyd’s keynote at SXSW. Holly Clark enters this conversation explaining why she chringes when she hears the word ‘digital literacy’.

In Clark’s post, she states that literacy is about the ‘competence of knowledge’. It is that thing required to make meaning. She then goes on to argue that what is at stake is not necessarily the competence to make meaning, but rather the ability:

What students don’t possess most often is a not digital literacy, but rather digital fluency. As educators if we spend our time talking about literacy – and what feels like ONLY literacy – and we leave out the more educationally important idea of fluency we might be doing students an injustice. Fluency is the term that SHOULD be at the heart of everything we are talking about. It is where the transfer of knowledge happens, where kids apply that literacy they developed without our help, and get past the making meaning stage to a place where they are transferring knowledge on their way to becoming effective digital citizens and learners.

I agree with what she is saying, it is not our knowledge of these things that matters, but rather application of such knowledge. Therefore, I can know about two-factor authentication, which by her definition would be a part of being ‘digitally literate’. Tick. However, unless I actually apply two-factor to each of my accounts then it is of little use.

The particular example that Clark gives is that of searching. As she explains, you cannot have an knowledge of a search (or a query) unless you understand the consequences and to do so you would need to be fluent, not literate.

The question we should be asking as educators is – are they fluent in search? Do they know how to craft a search that will deliver to them a page of really meaningful and purposeful results – results that come from mostly credible sources? Do they have the fluency to evaluate the information the search produces. I promise you the answer is no in 98% of cases. There is a fluency to search, to knowing what happens when you add quotes, or the minus symbol, or keywords and how this all affects the end result. This is the digital fluency of understanding the intended message (or query) you are delivering to Google.

As Clark highlights, simply knowing to use quotation marks is not enough, we need to understand why this is the case.

Although I am not as confident as Clark to call out ‘98%’ as the number, I think that this difference between knowing and understanding is a consequence of a tick-box approach to many of these things. There are great programs like eSmart’s Digital License, which help build knowledge. However, like many licenses in life, it can be a means to an end. The question is often what happens once they have their license that matters. Again, if they find out about the importance of two-factor and security, but continue to use their dogs name as their password, then it is to little avail.

My concern with Clark’s argument is that she puts ‘digital literacy’ to the sword, replacing it with ‘fluency’. This is problematic on two fronts. Firstly, the concept of literacy is not fixed. Secondly, we are better considering the plurality of digital literacies.

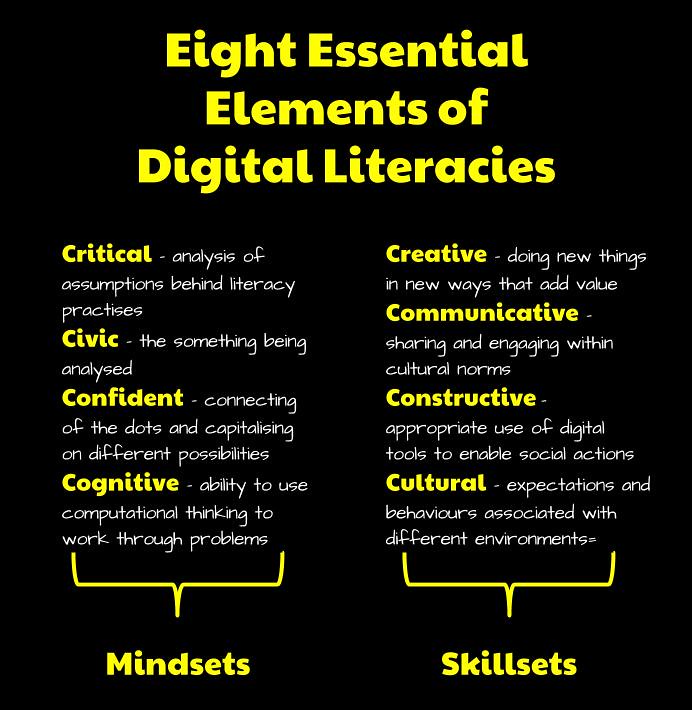

In The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies, Doug Belshaw suggests that literacy involves using a tool for a particular purpose.

Before books went digital, they were created either by

using a pen or by using a printing press. These tools are technologies. Literacy, therefore, is inextricably linked with technology even before we get to ‘digital’ literacies.

This use is always a social process that is contained within a context, for “in isolation, an individual cannot be literate at all.”

Adding the ‘digital’ modifier increases the ambiguity associated with the situation. Instead of providing an overarching definition, Belshaw provides eight elements to make sense of the different incidences of digital literacies.

- Cultural – the expectations and behaviours associated with different environments, both online and off.

- Cognitive – the ability to use computational thinking in order to work through problems.

- Constructive – the appropriate use of digital tools to enable social actions.

- Communicative – sharing and engaging within the various cultural norms.

- Confident – the connecting of the dots and capitalising on different possibilities.

- Creative – this involves doing new things in new ways that somehow add value.

- Critical – the analysis of assumptions behind literacy practises

- Civic – the something being analysed.

What is important here is that we cannot meaningfully consider all these elements at once. Each offers the possibility of digging deeper or stepping back.

Take for example searching online. We can confidently search for information. This is what Clark captures with her discussion of ‘fluency’, However, this does not necessarily capture the critical side of search and algorithms. Interestingly, Clark makes mention of the plurality of literacies, but never quite explains what she means.

In the end, what is needed in this area is more conversation. It is complicated. It is contested. As always, comments, criticism and cringing welcome.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.