flickr photo shared by mrkrndvs under a Creative Commons ( BY-SA ) license

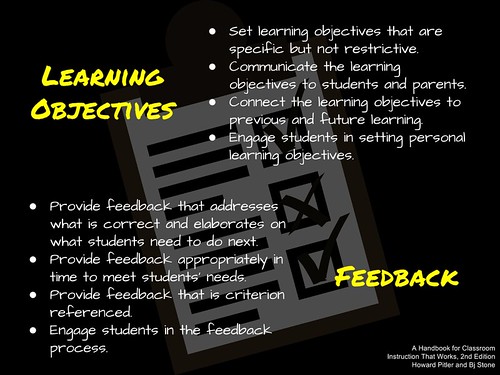

My school recently started the process of implementing a new instructional model. At the heart of this model is Howard Pitler and Bj Stone’s book A Handbook for Classroom Instruction That Works. Developed from the work of McREL and Robert Marzano, the book unpacks the different facets involved in embedding a culture of instruction. This is the third post in a series looking at cooperative learning.

In a post discussing learning intentions, Chris Harte splits the learning process up between skillset, mindset and toolset. This divide is a useful way of appreciating the environment offered by by Pitler and Stone, with objectives and feedback representing the skillset and growth and recognition representing the mindset. This leaves the toolset. In a separate post, Tom Barrett describes the toolset as,

Toolset (How you Get, Have, Use) – Means a set of widely accepted methods, techniques, models, approaches and frameworks that can create value in the chosen field.

In regards to the environment of learning, the main tool at play according to Pitler and Stone is cooperative learning.

At its heart, cooperative learning focuses on developing a culture of collaboration. In Alfie Kohn’s argument against competition, he captures a definition of collaboration, suggesting that:

Learning at its best is a result of sharing information and ideas, challenging someone else’s interpretation and having to rethink your own, working on problems in a climate of social support.

According to Kohn, this can occur at any year level and in any subject. However, there are a range of challenges to make this all happen, including group sizes, process and space.

Models, such as Tuckman’s stages of group development, which focuses on forming–storming–norming–performing, provide support in regards to process. While those like Cathy Davidson provide an intentional set of practises devised to foster perspective. Also, Mia MacMeekin provides a range of strategies and activities to refocus groups:

Providing his own take on things, Alex Quigley outlines a set of essential steps, including a focus on time, purpose and assessment.

In regards to the size of groups, there are those, such as David Weinberger, who suggest the strength lies within the networks, with “the smartest person in the room being the room.” The focus in this circumstance (which is often digital) is on the whole, rather than the particular strength of the individual. In relation to actual size, Donald Clark argues that three is the optimal number for small group work, while Jennifer Mueller suggests that groups above five starts to challenge motivation.

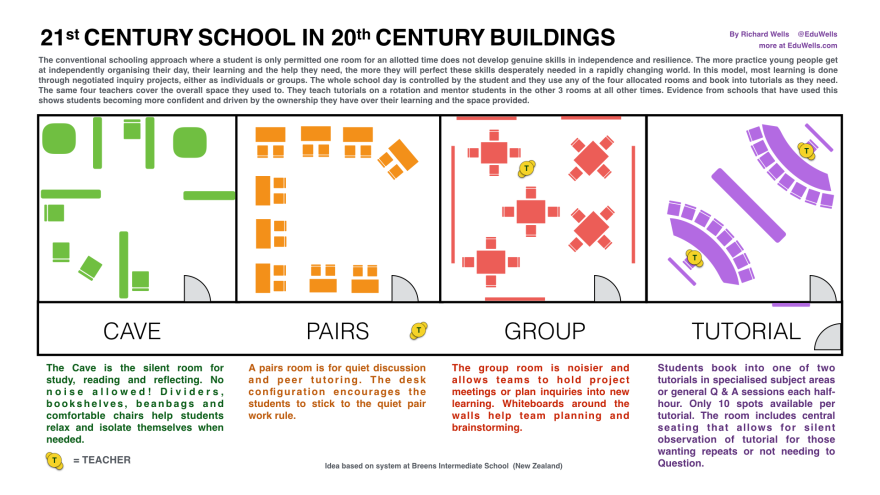

An influence on the size of groups is the structure of the space. This dilemma is clearly depicted by Richard Wells investigation into environments,

What is significant about Wells’ diagrams is the dependency on flexibility of furniture, as well as the ever changing role of the teacher. Kohn captures this best situation well when he says, “a classroom where collaboration is taken seriously is a place where a visitor has trouble finding the teacher.”

Coming at the problem of group work, Alex Quigley offers up definitive set of questions to help teachers reflect on their practise:

- What is the ideal number for the group size for this task?

- Are students clear about what effective collaboration looks like and sounds like?

- What are the group goals and individual goals for this task? Are they clear to the students?

- How are you going to fend off ‘social loafing’?

- Should personality differences influence our grouping decisions? Are there introverts in the classroom that should receive particular attention as we decide upon grouping students?

- How should we group in relation to ability or skill levels? Are the groups separate by ability or mixed, or randomised? Does this make a difference?

The greatest challenge though with all of this is the question of accountability. It is this that cooperative learning captures.

According to Pitler and Stone, cooperative learning groups emphasize positive interdependence. This involves finding a balance between group work and individual accountability. As they explain,

Small-group work is valuable, but cooperative learning, with elements of positive interdependence and individual responsibility, is the strategy that rises to the level of significance.

One of the biggest quandaries with accountability and responsibility is making sure that each member has an equal workload. This equality though needs to go beyond simply prescribing roles. With a focus on group objectives, the attempt to capture a true sense of individual accountability is best done through the use of both formative and summative assessment. This can only occur though when cooperative learning is both consistent and systematic. (See Charles Garcia’s post for a further discussion of this.)

An example of cooperative learning is the Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS). Devised by the ATC21s group, CPS focuses on the Conceptual Framework for Collaborative Problem Solving, highlighting the skills and perspective that people bring, rather than the jobs they do. Rather than splitting a task between members in order to do something more efficiently, the focus is on process and the skills brought to bare. Significantly, with CPS there is a focus on authentic tasks. It is for this reason that predefined roles and responsibilities are limited. Interestingly, the team behind CPS only works when a task is authentic. It could be argued that it is for this reason that CPS and therefore cooperative learning are essential skills for those entering the 21st century workforce.

So what about you? What have been your experiences cooperative learning and collaboration? How have you grappled with the challenge of interdependence? As always, comments welcome.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.