flickr photo shared by mrkrndvs under a Creative Commons ( BY-SA ) license

Today, I received notification that a case study I wrote for a special edition of the Southern Institute of Technology Journal of Applied Research (SITJAR) has been published. I feel a little out of my league. However, heutagogy is one of those topics that seems to go beyond leagues. Thanks as always to Stewart Hase and Chris Kenyon.

You can read my paper below, enjoy.

Abstract

Personal growth is often sacrificed at the expense of organisation reform. The modern challenge in creating more effective workplaces is providing meaningful time, space and opportunity for self- directed learning. A part of this change is fostering a culture of thinking. This is explored through a case study, reflecting on the co-creation of a conference presentation. This is not used as a representation of the how it is to be done, but of the complexities associated with collaborative learning. For there are many different models and methods for achieving the desired outcome of autonomous learning. Whether it be TeachMeets, Twitter chats or staff driven meetings, what is important is that learning is disciplined.

Introduction

Like the students we teach, teachers too have areas of interests that they often never get a chance to unpack, passions that never get explored, ideas that never properly get thought out. Although many discuss the benefits of Genius Hour for students, there is often little time, space and support for anything like this for teachers. Instead, meetings and professional development is often defined by perceived objective needs, rather than focusing on personal growth. As Matthew Kraft and John Papay explain,

We tend to ascribe teachers’ career decisions to the students they teach rather than the conditions in which they work. We treat teachers as if their effectiveness is mostly fixed, always portable, and independent of school context. As a result, we rarely complement personnel reforms with organizational reforms that could benefit both teachers and students. (Kraft & Papay, 2015).

The question that remains then is how might we build a culture of thinking that fosters autonomy in order to create a more effective workplaces?

Learning to Learn by Learning

One of the essential ingredients to teacher growth and autonomy is collaboration. David Weinberger makes the point that, through networks and the inextricable abundance of knowledge, “the smartest person in the room is the room” (Weinberger, 2011, p.12). This does not mean that simply being in the room is enough. For being a part of the room we are challenged to engage with others to build both physical and digital networks that make us all smarter. This involves, what Mike Wesch describes as, going from being knowledgeable to being knowledge-able (Wesch, 2009).

A case study of such learning is the collaborative development with Steve Brophy of a presentation for Digital Learning and Teaching in Victoria 2014 Conference. As teachers we often talk about collaboration, yet either avoid doing it or never quite commit to the process. Some may work with a partner teacher or in a team, but how many go beyond this? When do we step out of the comfort zone and the walls of our schools, to truly collaborate in the creation of a project or a problem? Immersing ourselves in what David Price describes as ‘self-determined peer learning’ (Price, 2014, p. 115)>

Having spoken about the power of tools like Google Apps for Education (Davis, 2014a) to support and strengthen collaboration, communication and personalised learning, I realised that what was needed to take the next step was to actually do it. Mindful of taking the easy path of simply working �with a colleague from my own school, I sort out someone different who I could co-create with, but to also be knowledge-able through the use of various tools to actually collaboratively co-create a presentation from scratch.

Brophy and I initially met online. A modern trend. The Ed Tech Crew podcast ran a Google Hangout at the end of 2013 focusing on the question: what advice would you give a new teacher just appointed as an ICT coordinator? (Richards & Branson, 2013) I put down my thoughts in a post (Davis, 2013), Brophy commented and wrote a response of his own (Brophy, 2014). It was these two perspectives, different in some ways, but the same in others, that brought us together.

From that point we built up a connection online – on Twitter, in the margins of a document, within blog posts, via email – growing and evolving the conversation each step of the way. For example, Brophy set me the 11 question blog challenge (Davis, 2014b), which he had already taken the time to complete himself (Brophy, 2014b). We met face-to-face for the first time when we both presented at a Teachmeet at the start of 2014.

What clicked in regards to working with Brophy was that although we teach in different sectors, coming from different education backgrounds, we shared an undeniable passion – student learning and how technology can support and enhance this, or as Bill Ferriter would have it, “make it more doable.” (Ferriter, 2014, p.14) We therefore put forward our proposal for the 2014 Digital Learning and Teaching Victoria Conference around the topic of ‘voices in education’. Interestingly, once the submissions were accepted, those wishing to present, were encouraged to connect and collaborate with other members in the stream, rather than work in isolation.

In regards to planning and collaborating, it was rather ad hoc. A few comments in an email, brainstorming using a Google Doc, catching up via a Google Hangout, building our presentation using OneNote. Most importantly though, there were compromises at each step along the way. This was not necessarily about either being right or wrong, but about fusing own ideas with those we had collected along the way. So often presentations are planned with only our own thoughts in mind. Although we may have ideas about our intended audience, nothing can really replace the human element associated with engaging with someone else in dialogue.

In regards to the substance of our actual presentation, I put forward the idea of dividing it into Primary and Secondary. However, as things unfolded, this seemed counter-intuitive, for voices are not or should not be constrained by age. So after much discussion we came upon the idea of focusing on the different forms of connections that occur when it comes to voices in and out of the classroom. We identified three different categories:

- Students communicating and collaborating with each other,

- Students and teachers in dialogue about learning,

- Teachers connecting as a part of lifelong learners.

A part of the decision for this was Brophy’s work in regards to Digital Leaders. (Brophy, 2014a; Jackson, 2014). This focus on students having a voice of their own really needed to take some pride of place, especially as much of my thoughts had been focusing on the engagement between students and teachers.

The next point of discussion was around the actual presentation. In hindsight, I fretted so much about who would say what and when, as well as what should go in the visual presentation. This is taken for granted when you present by yourself for in a traditional lecture style presentation you say everything. However, when you work with someone else it isn’t so simple. The irony about the presentation was that so often plans were often dispersed in an effort to respond to the moment. Sometimes the worst thing you can do is to stick to the slides, because somehow that is the way it has to be, even though that way is often a concoction in itself. The other thing to be said is that the slides for the presentation also allows people to engage with the presentation in their own time, in their own way. I sometimes feel that this is a better way of thinking about them.

�The best aspect about working collaboratively was that by the time we presented we knew each others thoughts and ideas so well that it meant there was something that one of us overlooked then the other could simply jump in and elaborate. This was best demonstrated in our shortened TeachMeet style presentation, where instead of delivering a summary of what we had already presented earlier in the day, we instead decided to go with the flow. The space was relaxed with beanbags and only a few people, therefore it seemed wrong to do an overly formal presentation. Focusing on the three different situations, we bounced ideas off each other and those in the audience.

What stands out about the case in focus is that much of it occurred both online and outside of regular school hours. This is all well and good, but the question that remains is how we make such practise sustainable? How might we support teachers in taking more ownership over their own learning?

Culture of Thinking

In Ron Ritchhart’s book on creating a culture of thinking, he touches on three essential beliefs: (i) non-direction, (ii) pressing for thinking and (iii) supporting autonomy.(Ritchhart, 2015, p.218) The case study presented covers each in its own way. However, what is important is that there are many different models and means for achieving this mix.

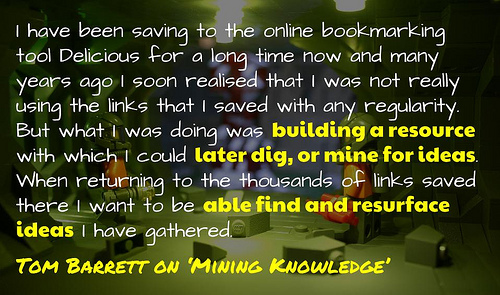

As I search back through the links I have collected over time, I find teachers and administrators exploring models for learning, each touching on these elements. In a post about enlivening whole school professional development days, Edna Sackson talks about empowering teacher voice by giving them all a chance to present, rather than simply bringing in outside providers. (Sackson, 2014) Inspired by the work of Daniel Pink, Chris Wejr shares how he incorporated time for teachers to tinker into the day by providing them release. (Wejr, 2013) While reflecting on learning about Little Bits, Jackie Gerstein unpacks the importance of educators openly being lead learners. (Gerstein, 2015) Taking a different stance, Tom Whitby wonders with the rise of unconferences, whether the traditional conferences are relevant anymore? (Whitby, 2014) Discussing much the same point, David Price touches on potential of different models of self-determined learning, such as TeachMeet events and Twitter Chats, which are threatening traditional models of learning. (Price, 2014) While unpacking the conventional workshop, Chris Kenyon demonstrates how using a heutagogical approach learners can be supported in developing their own solutions. (Kenyon, 2014)

What each of these examples demonstrates is that there is not one model that fits every context and nor should there be. Every situation is unique and has its own needs and requirements. Beyond actually incorporating such opportunities within schools, the challenge moving forward seems to be how to best recognise such opportunities in more formal environments? How might we, as Will Richardson asks, transition from master knowers to master learners? (Richardson, 2015). The one guarantee is that no matter what model is implemented, learning must be disciplined.

References

Brophy, S. (2013). Reflections of an lLearning coordinator. transformative LEARNING. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from https://stevebrophy.wordpress.com/2013/12/29/reflections-of-an-elearning- coordinator/

Brophy, S. (2014a). Digital Leaders. transformative LEARNING. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from https://stevebrophy.wordpress.com/2014/06/09/digital-leaders/

Brophy, S. (2014b). 11 questions. transformative LEARNING. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from https://stevebrophy.wordpress.com/2014/01/31/11-questions/

�Davis, A. (2013). I was just appointed ICT co-ordinator, Now What?. Read Write Respond. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from http://readwriterespond.com/?p=118

Davis, A. (2014a). In search of one tool to rule them all. Read write respond. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from http://readwriterespond.com/?p=109

Davis, A. (2014b). 22 Questions …. Read write respond. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from http://readwriterespond.com/?p=95

Ferriter, B. (2014). Do we REALLY need to do new things in new ways?. The tempered radical. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from http://blog.williamferriter.com/2014/04/27/do-we-really-need- to-do-new-things-in-new-ways/

Gerstein, J. (2015). Educator as lead learner: Learning littleBits. User generated education. Retrieved 31 May 2015, from https://usergeneratededucation.wordpress.com/2015/02/23/educator-as-lead-learner-learning- littlebits/

Jackson, N. (2014). OzDLs | digital leaders Australia – Empowering young people with technology.Ozdls.com. Retrieved 24 May 2015, from http://www.ozdls.com/

Kenyon, C. (2014). One way of introducing heutagogy. In L. Blaschke, C. Kenyon & S. Hase, Experiences in self-determined learning (1st ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Kraft, M., & Papay, J. (2015). Developing workplaces where teachers stay, improve, and succeed. Shanker Institute. Retrieved 30 May 2015, from http://www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/developing-workplaces-where-teachers-stay-improve- and-succeed

Price, D. (2014). Heutagogy and social communities of practice: Will self-determined learning re- write the script for educators?. In L. Blaschke, C. Kenyon & S. Hase, Experiences in self- determined learning (1st ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Richards, T., & Branson, D. (2013). Xmas Google Hangout. Edtechcrew. Retrieved 30 May 2015, from http://edtechcrew.net/podcast/ed-tech-crew-238-xmas-google-hangout

Richardson, W. (2015). From master teacher to master learner. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sackson, E. (2014). Personalised learning for teachers…. What Ed said. Retrieved 23 May 2015, from https://whatedsaid.wordpress.com/2014/08/09/personalised-learning-for-teachers/

Weinberger, D. (2011). Too big to know: rethinking knowledge now that the facts aren’t the facts, experts ere everywhere, and the smartest person in the room is the room. New York: Basic Books.

Wejr, C. (2013). Creating time for teachers to tinker with ideas #RSCON4 | The Wejr Board. Chriswejr.com. Retrieved 31 May 2015, from http://chriswejr.com/2013/10/05/creating-time-for-teachers-to-tinker-with-ideas-rscon4

Wesch, M. (2009). From knowlegable to knowledge-able: learning in new media environments. The Academic Commons. Retrieved 31 May 2015, from http://www.academiccommons.org/2014/09/09/from-knowledgable-to-knowledge-able- learning-in-new-media-environments/

Whitby, T. (2014). Are education conferences relevant?. My Island View. Retrieved 31 May 2015, from https://tomwhitby.wordpress.com/2014/02/08/are-education-conferences-relevant/

�

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.