From Little Things, Big Things Grow

ICT has a way of finding people. My personal background is as an English and History teacher. However, I have always had some affiliation with technology, whether it be sitting in on the ICT committee or being a part of the pilot program involving student laptops. A few years ago, an opportunity arose to teach Multimedia and Robotics to students in Years 7 and 8. My school had made a decision to teach ICT and Home Economics, instead of other more traditional technology subjects, such as Woodwork and Metalwork. With no one in the school ‘qualified’ to teach ICT, initially it had been shunted around between the Maths and Science team, based on Robotics. During this time, I had developed a bit of a reputation as a bit of an ICT problem solver. If someone had a problem, I was seen as the one to solve it. Whether it be getting students on the now defunct Ultranet or how to use the interactive whiteboards that were set up in every classroom, I was the go to. Subsequently, I was asked to take on the teaching of ICT within the school.

Coming from an English background, the first thing that I felt needed to change was the use of conventional workbooks. Past teachers had the students continuing to work on paper, I decided to approach the subject from the point of view of trial and innovation. I wanted the students to leave my class with skills that I felt that they could take into their other classes. I decided therefore to use Microsoft Word. Initially this was a real success, students learnt how to utilise text styles and other such guides and shortcuts. However, the age old problem soon arose around the ‘collection’ of workbooks. For whatever reason, it would take students nearly ten minutes to complete the laborious task of copying their workbook into a shared folder on the school network. Something that I could do in ten seconds. In addition to this, there were some students who managed to ‘mysteriously’ lose their work. This became a particular problem with the arrival of student laptops as the standard approach to most system problems by the school technicians is to simply re-image the computer, therefore wiping all memory. I therefore made the decision that we needed to find a better solution. After exploring the potential of Evernote and Onenote, I decided to go with Google Drive (nee Docs) as my solution. My concern with Evernote was the limitations in regards to formatting, although it is great for note-taking tool, I felt that it was too limited in regards to fonts, headings and other such stylistic elements. I also felt that Google would be easier to use with the students. From here, the ball has rolled and the use of Google Drive has progressively spread from one classroom to infiltrating many elements of the school.

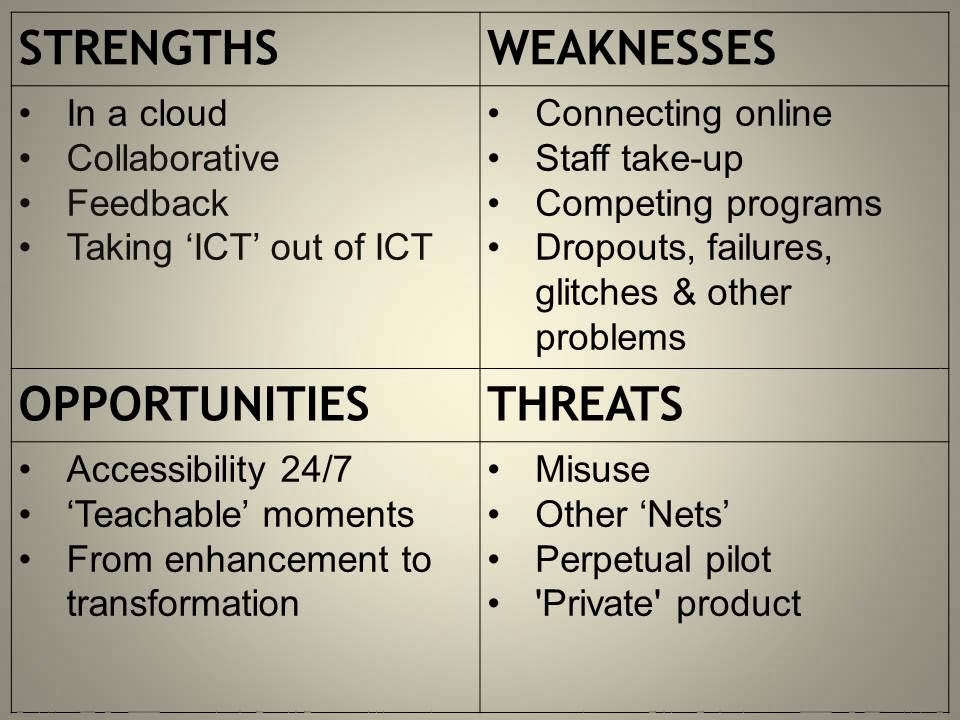

To me, the best way to look at the progression from Google Drive from a program used to create a digital workbook to a program that has slowly infiltrated all aspects of school is through a SWOT analysis. Therefore, breaking it down into its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

‘S’ Stands for Strength

In a Cloud

In my view, one of Google’s biggest strengths is that it lives in the cloud. No longer do we have the myriad of reasons that endlessly abound the classroom, such as ‘I left it at home’ or ‘it did not save’. This is best summed by the viral image of ‘10 Sentences Google Teachers Never Hear’ which lists statements such as: “I finished my paper, but it’s on my computer at home” and “I tried to email this document to myself so I could print it out at school, but its not in my inbox”. This is made even more pertinent with the progressive move away from desktops to personal devices, such as laptops and tablets. Moving away from a school network to the web is surely inevitable.

Collaboration

One of the most powerful attributes associated with Google Drive is the ability to collaborate. Although the most obvious point of collaboration is between students, Google also provides a real and meaningful opportunity to collaborate between staff. The share options in Google allow for so many different methods for sharing, whether it be adding someone else to the document or simply sharing the link to the document. Some examples of documents and tasks that I have used collaboratively include:

- a bookclub document added to by all group members

- reading conference notes shared between student and teachers

- study club list where names are added by any staff, anywhere, anytime

- comment banks and subject blurbs shared with staff

Feedback

In addition to collaborating, another powerful attribute is the ability to provide feedback. One of the limitations with conventional teaching is that to provide students with feedback, you need to collect their books. Sometimes this is not practical as they may still be working on something and it can be a difficult task finding space for a million books on a teachers already crammed desk. Google has provided the means in the classroom to overcome this. Some examples of documents and tasks that I have used to provide feedback include:

- class workbooks providing a dialogue between staff and students through the ‘comments’ function. These comments are often a mixture of either overall comments, as well as targeted comments done by highlighting work in question and just commenting on that.

- a class presentation where students posed questions on each others presentations by highlighting particular points in question. This often led to students who were being questioned further elaborating their understandings, therefore showing a deeper knowledge and understanding.

- curriculum documents, which not only allowed people to collaboratively add information, but allowed each member to provide comments on what did and did not work at they go along.

- various forms allowing staff and students to ascertain information and present it in a second, such as a PE skills classification where students completed a quiz to create a set of data to discuss as a class.

Taking ‘ICT’ out of ICT

One of the biggest lessons learnt from the Ultranet is that if something does not make some sort of sense at first glance then it takes a lot of convincing, as well as tedious and repetitious explanation, to get staff and students on board. From all the feedback that I have gathered in regards to Google Drive, the biggest positive that is shared is how easy it is to use. It is intuitive and as easy as you will get. I have had to explain the difference between the ‘shared with me’ and ‘my drive’, as well as remembering to share documents, such as workbooks, with teachers. However, that seems to have been the extent of my problems. In the end, Google Drive allows ICT to move away from the restrictive concept of a ‘subject’ to a tool for learning used across all subjects.

‘W’ STANDS FOR WEAKNESSES

Connecting Online

Behind every great ICT program there is someone else doing a whole lot of work in the background. For ICT to work properly, sadly, it usually involves someone else doing, what I term, the grunt work. This was the case with the Ultranet and is definitely the case with Google Drive/GAFE. Some staff and students have issues with remembering another username/password. Also, new years create new problems.

Staff Take-up

One of the biggest difficulties with anything relating to ICT is getting everyone on board. Although students are usually very quick to jump into the potential of new programs and technologies, staff are often not so keen. They often question the value of changing and simply see it as a hassle. Often it is seen as an tool rather than a potential for the modification and redefinition of learning and teaching.

Competing Programs

Associated with taking up new programs, is the perception that ‘other’ programs are better. Although I am not saying don’t use other programs, competing views about how things should be done only undermine the overall take-up and wider support. For example, in my school there is a group of teachers who love using Dropbox for everything and anything. The one benefit that they see is that they are able to create curriculum documents and embed additional files within it. Therefore, for them, Dropbox provides a single place to store all materials. The common view is that Google does not provide this functionality. However, one of the catches to this is that Google Drive/GAFE provide a considerable allocation of space (30GB for GAFE vs. 2GB for Dropbox)

Dropouts, Glitches, Failures & Other Such Problems

Another inhibiting factor in regards to the take-up of Drive is that unless it works 100% of the time, EXACTLY the way people expect it to, then there are some teachers and students who just run. I have some students in class who will tell me ‘the Internet is not working’ every five minutes, only to respond the next second that it is working again. Apprehensive staff on the other hand only get more tense when what they want does not work. Although it may well be working, they can often lack the patience to step back and identify a plausible solution to the issue at hand. Another problem that often raises its ugly head is the difference between the imagined and the reality. This is something that I saw show itself with the Ultranet, with some staff wondering why the Ultranet would not do what they thought it should do. The hardest thing in this situation is how some teachers ‘expect’ something to run is not in fact how it does run. Some such issues include problems with formatting when converting documents from Microsoft to Google Docs, as well as manipulating tables within documents, especially on an iPad. In the end, there are times when you need to find the right tool for the job and for some Google might not be that tool?

‘O’ STANDS FOR OPPORTUNITIES

Accessibility 24/7

No longer is there a need to haul home endless amounts of student workbooks. With the increasing access to the internet, Google provide access on any device, anytime. With the influx of devices, whether it be a laptop, desktop or mobile, Google also provides the ability to sync information.

‘Teachable’ moments

Google Apps for Education even more so than Google Drive by itself allows for a contained environment in which to promote the appropriate use of technology, a place for discussing the digital trail that we continually leave behind in the modern age. A part of this process is also notifying and educating parents and making sure that the appropriate policies and documentation are in place.

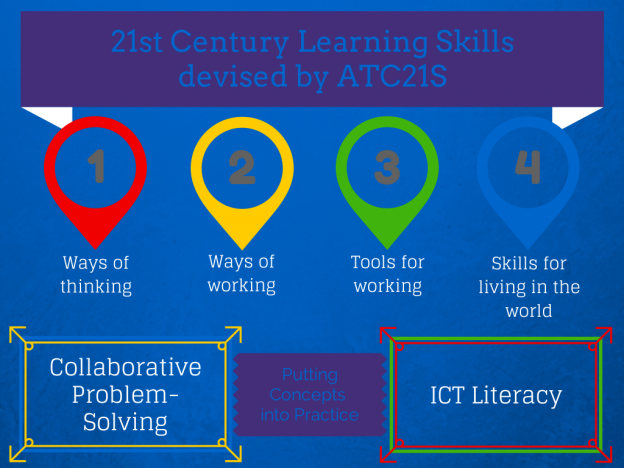

From enhancement to transformation

At present, much of Google’s use in the school is at an enhancement level, to borrow from the SAMR model, with much of the use simply replacing what is done elsewhere. Although there has been some improvement with efficiency, there has been little change in the way things are done. That is the next challenge, to actually modify tasks and the way things are done and to progressively move towards the previously inconceivable. Although such a move would not solely be done through ‘Google’, it does provide a foundation for much of what can be done.

‘T’ STANDS FOR THREATS

Misuse and Abuse

One of the biggest threats for many is the use and misuse of technology. Google is not absolved of this. I have had examples of students creating their own document and sharing it amongst each other, conducting chat through it. My concern with this is that if you block things or lock them down, then students will simply find something else. Can you really block everything? And is this even the solution anyway? In my view, students will always find a way. Do we let them wait until they get into a workplace where they write something inappropriate and learn that way? Students need to learn the consequences for their actions, not simply a list of abstract rules to live by. You can use this website, but you can not use that. I think that

Sir Ken Robinson summed it up best recently saying, ‘If you sit kids down, hour after hour, doing low grade clerical work, don’t be surprised if they fidget.’

Other Nets

My school has an intranet which was originally used to store documents and information. Over the years there has been a progressive movement away from using this. However, there are some people with vested interests who are unwilling to let go of the past.

Perpetual Pilot

There is a danger of what

Tom March said in his keynote a few years ago of waiting for the next best thing. I understand that you need to trial something for a small amount of time. However, in my view, at some point a stronger commitment needs to be made.

Can Google be Trusted?

There is a perception by some that Google can’t be trusted. “Will this not open our data up to the wider world, making it accessible to anyone and everyone.” Clearly, this is not the case with Google Apps for Education, where the school has control over both accessibility and content. However, as a corporation, I don’t know if Google can be trusted? Their history of dropping applications leaves many sceptical, while the amount of data that they seemingly collect leaves some questioning why.

Coming back to the village …

In the end, the question that needs to be asked, if it is not Google, then what? I’m ok with not using Google, but what are we going to use? One thing that Ultranet has made aware, doing nothing is not an option. I think that the challenge is to move beyond looking at everything as a problem and instead consider things as hurdles. Associated with this, I think that in a school environment, everyone has a responsibility to help everyone else, because it takes a whole community to create a digital village and that is where the future is.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.