What is the classroom of the future? We so often talk about change, let’s say 20% at a time. The challenge with this is that we often have in mind a particular model or space, however such ideals are not always ideal. I think one of the biggest challenges is having a consistent why as a starting point for further conversations.

I respect that it can be difficult to work collaboratively with each new staff or student to explicitly incorporate their particular thoughts and experiences, but it is important to provide a clear and compelling narrative that sits at the heart. This is often captured in the form of values that everyone comes back to. The challenge with such an exercise though is to come back to and refer to these regularly, to incorporate these into everyday thinking.

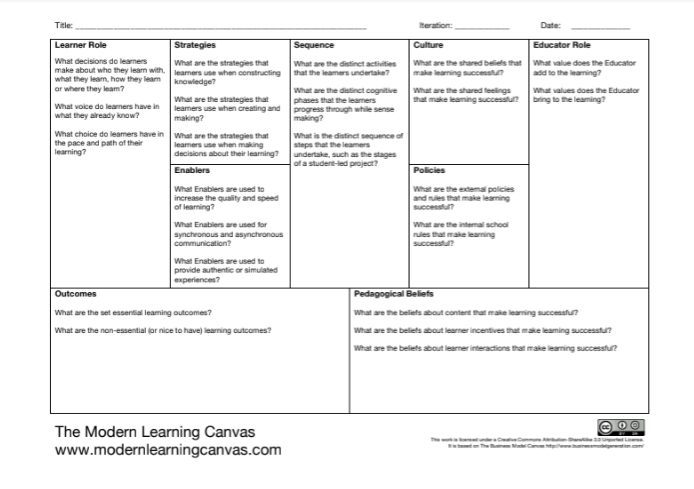

The issue is that too often decisions based on what is deemed to provide the highest impact or who is paying. These compromises can also come in regards to choice of tools or learning spaces. The challenge with all of this is being more informed about the intent behind such decisions and where they fit within the overall values. A useful thinking tool to help with this is the Modern Learning Canvas. Based on Business Model Canvas, the Modern Learning Canvas is broken into eight parts and helps capture a wider view of a context and situation.

The canvas allows users to drill down and focus on particular parts of the canvas, at the same time, considering the wider implications.

As an example of such fluidity, consider inquiry and its many flavours, whether it be problem-based, project-based or challenge-based. The question I feel is not which one is right, but rather what is the particular intent and who does this marry with the wider context. This challenge is addressed neatly in Peter Skillen and Brenda Sherry’s image which instead places all the ingredients on a scale.

Curriculum standards are a best guess for the future. The question is how to own this future. Take the digital technologies curriculum. Often people jump to particular outcomes or ideas, whether it be robotics, coding or ICT. However, it has the prospect of being far more open than this. In addition to just focusing on digital technologies, it can also be integrated with other areas. Anthony Speranza captures this possibility through the use of hexagonal planning as a narrative device.

The danger with all of this is pushing hard against the dominant narrative. Although lean methodologies prescribe testing new ideas, going wholesale can be like taking snow to the tropics, nothing more than an exhausting gimmick. Although it may offer a sense of alternative, this is simply undone when students return to the dominant model in the next class.

In the end, I am happy to imagine a day made of glass or coalescent spaces, but my hope for the classrooms of the future is one where there is more awareness and understanding about what occurs and the decisions that may have informed them.

As always, thoughts and comments welcome.