If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

There seems to have been a few blogs bouncing around in my feeds of late. These include Deb Hicks‘ ‘Why Blog’, Tom Whitby’s ‘Why Blogs and Who Needs Them Anyway’ and Peter DeWitt’s ‘The Benefits of Blogging’. It kind of occurred to me that I hadn’t really ever stated, nor really thought about, why I have chosen to blog. I have therefore decided to have a go at providing some of my reasons:

- Scratching an itch. Often while reading, there are things that stick out, that prop the ears, the spike the imagination, that remain like an itch. A blog is a way of responding to these things, somehow alleviating the irritation.

- Being connected. I love being connected, following various threads of thought, commenting, tweeting and reaching out to others, but sometimes a responding needs to be something more substantial. A blog is one avenue that allows this.

- Critical engagement. I read on the wall in a coordinators office the other day the statement that ‘behaviour unchallenged was behaviour accepted’. I kind of feel that the same can be said about ideas. Online environments allow for encounters of all kinds, a part of this meeting of ideas is a need to critique. Not so that we may be ‘right’, rather that we may be wrong, in order to become better. As Seth Godin puts it in talking about ‘failing often’: “Fail often. Fail in a way that doesn’t kill you. This is the only way to learn what works and what doesn’t.”

- Life long learning. What I love most about writing a blog is that it allows a space to follow through on different points of learning, a kind of thought experiment, a place to grow ideas, in order that I may develop further. At its heart, a blog allows for the cultivation of seeds of inquiry, exploring and discovering what they may produce.

- Lead by example. J. Hillis Miller once posed the question: “How can we teach reading if we are not readers ourselves?” I think the same argument can be applied to tools for working in the 21st century. I do not think that ‘teachers’ have to be in control, but they do need to be the ‘lead learner’ as Joe Mazza would put it. To me, that means getting involved from the inside – testing, trialling, questioning, understanding – not just commenting from the outside, and especially not just when you are forced to.

Here are some of the reasons why I choose to blog. Although I am sure there are more, it is at least a start. So what are the different reasons you blog?

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

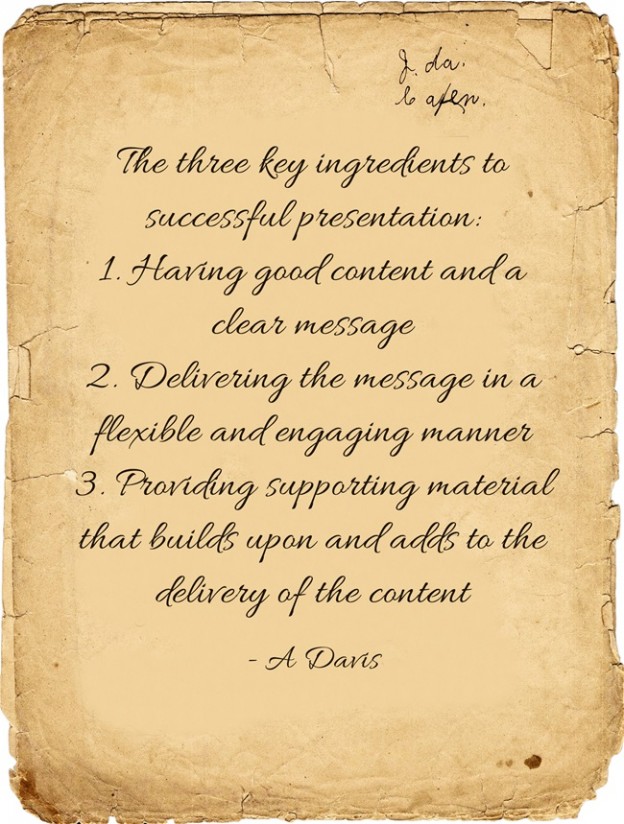

The creation of a presentation is more than just images and text on a slide. To effectively engage an audience and convey powerful messages, you need to consider those messages and specific design principles that will allow present your information in the most effective manner possible.

I will now build upon each of these things.

Content

Delivery

Supporting Material

Another way in which supporting materials are important is that they allow the dialogue to continue on. Recently whilst trawling my Twitter feed I read a tweet from Troy Moncur.

What struck me about the tweet is that with the advent of various social media platforms, presentations now have the ability to carry on long after the lights have been turned off. They no longer need to finish, rather they now have the ability to link from one presentation to the next.

Conclusion

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

The unconnected educator is more in line with the 20th century model of teacher. Access to the Internet is limited for whatever reason. Relevance in the 21st century is not a concern. Whatever they need to know, someone will tell them. If they email anyone, they will follow it up with a phone call to make sure it was received.

Reading, a Sum of Many Interconnected Parts

21st Century Learning, A Whole or Many Parts?

Ways of thinking. Creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, decision-making and learningWays of working. Communication and collaborationTools for working. Information and communications technology (ICT) and information literacySkills for living in the world. Citizenship, life and career, and personal and social responsibility

Take for example the failure of interactive whiteboards. I was once privy to an inspiring presentation run by +Peter Kent for Promethean. His main point was that the interactive whiteboard offered an opportunity to modify the way we teach and the way students learn. Take this possible sequence of events as a model: after brainstorming ideas, students are invited to come up to the board and engage with the content by reorganising the information, these choices are then used to develop a further conversations, such as ‘why did you make that choice’. This series of events shows the possibility of the interactive whiteboard to not only decentralise the classroom (at least remove the teacher from the stage), but also the ability to engage students in the critical question of ‘why’ they made the decision that they did. Sadly, from my experience, the use of IWB’s has never really gotten past using the boards as an overpriced projector, a part from those few cavaliers trying to lead the way. I feel that there are two things that have inhibited the take up of IWB’s by teachers. Firstly, many staff struggle to utilise the associated software to its full potential (this is often the biggest hurdle), but more importantly, there is often an inability to link the use of IWB’s with the skills of thinking and collaboration. Is it any wonder then why they have never really taken? (I am of the belief that many of the benefits of interactive whiteboards are slowly being undermined by the rolling out of 1 to 1 devices, see Rich Lambert’s blog on the matter.)

Thinking in the 21st Century

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

What’s in the Name?

Relationships, Just Not Like That

One Moment at a Time

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

Strength is in the Weakness

In my view, the strength of any team is not in the leadership group, although having strong leadership is important, rather it is in the supposed lower ranks, those individuals and stakeholders deemed to be at the bottom, and their ability to carry the overall vision for the organisation. To use a sporting analogy, it is often the depth of the reserves rather than the strength of the seniors that a teams metal is truly tested. With enough money, any team can buy enough players to be a good side, but to be a strong and successful side, it is the ability to stand up against injury and adversity which often decides between winning a game and maintaining long term success. This same mentality can be applied to the day to day actions in any educational environment. Often effort and money is put into key areas associated with big data, such as NAPLAN. However, it is those areas found in the margins of the curriculum, areas which neither provide clear measurable data nor any direct benefits, that the strengths and weaknesses can truly be tested. In the past I have written about the problems with reading conferences, another aspect often shunted from the day to day activities is that of goal setting and their role in supporting learning and development.

Not so Smart Goals

I have experienced many reincarnations of student goals during my time, from goals written with no students in sight to students being given five minutes to scribble down a few vague ideas on a piece of paper. What ties all of these experiences together is that they are all about students, but far too often not composed for students. I have lost count of the amount of times that I have had to work through the SMART acronym with students. It surely says something when students need to be reminded again and again what supposedly makes a ‘good’ goal. I find the most poignant attributes of the so-called SMART goals is the ability to be ‘measured’. I completely agree that a goal needs to be measured, that is not my qualm. However, far to often the data that students use to supposedly measure their goals is not their own. Although they can demonstrate some sort of measurable evidence, they have little ownership over it. They merely complete a task and receive their grade as some sort of just reward. For example, many students often speak of improving their grades or getting better marks, when sadly these grades and marks often only tell a minuscule part to the story of learning.

Another interesting aspect to student goals is the frequency which they are completed. In my experience, goals are often set once a semester, usually connected to the mandatory requirement to include them within reports. Little interest is given to following up and managing them. Associated with this, school diaries have seemingly morphed to contain a treasure trove of learning resources, from study tips to style guides. Squashed in there has been the attempt to provide some sort of structure of the whole process beyond the usual biannual occurrence. However, again this attempt to contain goals in a regimented manner is often lost on those to whom it matters most, the students.

In the end, the goals that students set are often lost in the system. Although they may make it into their reports or be filed for safe keeping, most students have little memory of what their goals were beyond the current set. Is it a surprise that student goals have little perceivable impact?

Life Long Teachers

On the flipside, the goals set by teacher are often no better. In the recent AEUVic industrial action, it was argued by the government that the whole incremental review system was flawed and that teachers were simply getting moved up each year whether they had earned it or not. Sadly, bringing in performance pay would only make a flawed system even more fractured. The problem with the current review process is that, like student goals, it is far from an organic process. Most schools (in Victoria) meet with staff twice a year. Once at the end of the first semester to set the Performance and Development plan and then again at the end of the year to review it. In addition to this, work is often done in teams to set goals based on the previous years data. This is all good, but it overlooks a major aspect of goal setting and that is the need to be timely. It must be said that over the last few years that there have been some great diagnostic programs, such as ePotential and the AITSL Self-Assessment Tool, developed to provide staff with feedback whenever they require it. However, these tools depend on one missing element, an intrinsic desire to forever be better.

There is a real push from some within education at the moment to push for more individualised professional development and to form more personalised Professional Learning Networks. (See for example Tom Whitby’s blog on ‘How Do We Connect Educators’ as well as Andrew Williamson’s presentation relating to PLNs.) I think though that one of the things inhibiting teachers from taking more ownership over their own learning and development is actually feeling confident enough to identify weaknesses without fear of retribution. I think that many teachers baulk at the idea of being truly honest out of fear that this may come back to haunt them if they were to apply for any sort of position of leadership. On the flipside, I think that there is also a fear among administration at times to allow any sort of freedom with staff as this may lead to precious professional development time being squandered. The problem that remains though is that some of the best professional development I have been to have been the sessions that I chose to attend in my own time, because I had an interest and I saw some worth in it for me. It begs the question, what will any goal achieve if it is not also attached to some sense of ownership?

Power is in the Program

One of the biggest frustrations that I have had with setting goals, whether it be personally or while supporting students, has been the fact that too often goals were developed and left at that. For example, student goals were set and the teacher kept a digital copy, while student would gain a print out. However, there was little feedback or progressive notes developed. This hurdle has been somewhat rectified with the recent inundation of collaborative tools that allow multiple people to be responsible for a single document. Whether it be keeping track of goals using Evernote, creating a Google Doc or simply sharing a document with Dropbox, there is no longer a reason why goals are not living and breathing documents. On a bit of a tangent, I am particularly interested in the work on Tony Moncur from Nichols Point Primary School who has started using the Ultranet (GenED 4.0) to manage and share student learning. I think that if there is anything to be said it is that technology allows the process to become more manageable and accountable. However, as I queried in my previous post, does technology really provide a complex solution or does it simply create a complicated answer that misses the real question, who are goals really been written for?

Student Goal Centered Learning

It is often spruiked that students are at the centre of all learning, then why aren’t goals as well? Surely if we are to make any move into the 21st century then we are going to have to learn to support learners in setting goals rather than just continue to write them for them. For how SMART are learning goals if they are not being driven by those individuals who they relate to? This may mean failing, but it also means allowing students to learn from those failures. If students are to truly be at the center then we need to support them in the process of taking ownership. How are you supporting your students with their goals and do they own them?

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

Reform needs Team

The River of Education

Complicated or Complex?

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.

This is a summary of the workshop that I presented at ICTEV13: IT Takes a Village

Discovery often starts with a problem. My problem was the use of mundane exercise books and worksheets. After exploring different potentials (Microsoft Word, Evernote and the Ultranet), I finally introduced Google Drive.

Some examples of how Drive has been used to transform learning include:

- access everywhere. With student laptops often re-imaged, work is not only continually backed up, but also accessible from any computer.

- the opportunity to work collaboratively. Some examples have included adding to a single document for book clubs, sharing student goals to all relevant stakeholders and staff working together on a curriculum document.

- the ability to provide flexible feedback. Whether it is a teacher commenting on a workbook anytime, students posing questions on a presentation or using Forms to ascertain different points of information.

On the other side of the coin, there are always hurdles faced when introducing a new application. Although students are usually quick to jump into the potential of new technologies, staff often question why they need to change, just look at the Ultranet. In addition to this, some staff feel that other applications offer more potential.

In the end, the question that remains is that if Google is not the tool to rule them all, then what? I’m ok with not using Google, but doing nothing is no longer an option.

Also published in Term 3 ICTEV Newsletter

If you enjoy what you read here, feel free to sign up for my monthly newsletter to catch up on all things learning, edtech and storytelling.