During a recent trip to Fiji celebrating our ten year wedding anniversary, my wife and I were lucky enough to visit a local primary school. It had roughly 200 students with a class for each year level. It is always interesting appreciating learning in different contexts. It highlights some things that we take for granted.

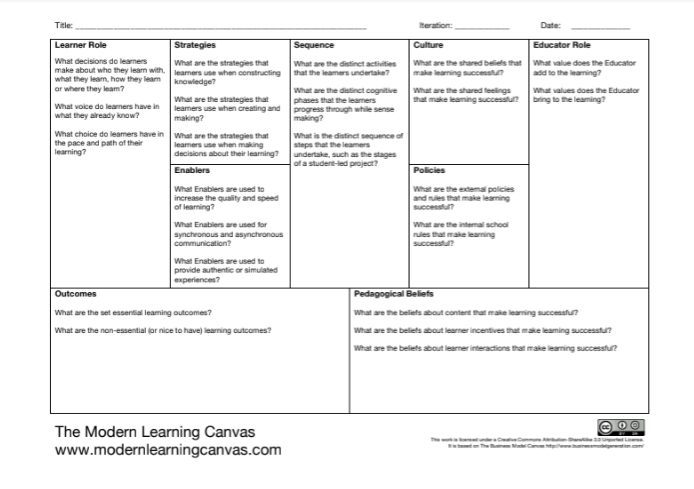

Using the lens of the Modern Learning Canvas:

Here are some of my observations of education in Fiji:

Roles, Strategies and Resources

Although the students we met were vocal, it was hard to decipher much choice or action over their learning. On the flipside of this, the educator’s role seemed pretty traditional with the teacher driving much of the learning.

It is always hard to properly judge learning by a walk through on a random day. What stood out though was the environments. The rooms were relatively dark, with the school building shaded by a veranda on one side and a hill on the other. The only cooling was via ceiling fans. I wondered what Stephen Heppell’s Learnometer would make of it?

The walls were covered with posters of various words and facts, while the chalkboards were full of formulas and activities. By their faded nature, I am not sure how many of the resources are changed around and it made me feel almost indulgent the way some teachers cycle through charts and posters. Having said this, I imagine that posters and paper would probably suffer from the humidity?

It is interesting to think about such technology as the chalkboard in regards to pedagogy, something Audrey Watters’ recently reflected upon. Although many people in the community had smartphones, there was limited access to devices in the classroom. No projectors. A few desktops in a room, but nowhere near enough for a class, let alone the school. Most teachers had a laptop though, which they would use to support learning. This reminded me of my own experience a few years ago and a post I wrote about what you could do with just one computer.

We were shown the library, which was a room with a few boxes of books around the edge. I did not notice many books in the classrooms. Although the government has a policy focusing on access and quality:

A reasonable collection of resources should comprise ten books per student.

It was not clear how this resourcing is funded. This also goes for the push for more devices too. Resourcing seems dependant on donations from companies, such as Vodafone.

Culture and Policy

With limited access to resources, more emphasis seemed to be put on speaking and performance. For example, students went through a rendition of a number of stories, such as We’re Going On a Bear Hunt, where the class was divided into two with one side repeating the lines of the other. A part of me wondered though if this was as much a reflection of the way in which they learnt in general, as music and oration seemed to be ingrained in a lot of what Fijians seem to do?

Each of the schools in Fiji seemed to have some religious affiliation. In part I would guess that this was based on the missionaries who set them up. In the school we visited this was evident in the bible verses posted on the walls.

On the flipside of this focus on culture, students were preparing for exams used to gain entry into secondary school. As with NAPLAN, The focus is on literacy and numeracy. Along with the supply of milk for Year One students, these were the only visible impacts of government intervention.

On a side note, the school had one of the most extreme emergency evacuation places, documenting what to do in the case of tsunami, earthquake, fire or mudslide. A reminder of nature’s presence.

Outcomes and Beliefs

It is interesting to consider Gert Biesta’s three arguments for a good education: qualification, socialization and subjectification. I felt the school touched on the first two of these. Speaking with some of the workers at the resort where we were staying the focus of education was very much about qualifications and what possibilities that might provide, while the posters discussing social media and alcohol touched on what it might mean to be a good citizen within the wider community. What this looked like in terms of outcomes was not so clear.

A Chalkboard and some desks is better than a tree in a field

When I think about other education environments I am always come back to a story, shared via Tom Whitby’s blog, involving teaching 230 children underneath a tree in Malawi. Although the school was not at those extremes – they had rooms and stable class sizes – it was a true reminder that sometimes we need to stop and appreciate the lot we have and make the most of it. What intrigued me is that as education becomes globalised, through such policy bodies as PISA, we overlook the expectations that can come with such changes. In some respect this is the purpose of the current project I am a part of, to bring schools up to a particular standard. Visiting Fiji has helped me think about some of the challenges and opportunities moving forward, as well as highlight some of my biases.

So what about you? Have you visited a school that helped challenge your thoughts and assumptions? As always, comments and webmentions welcome.